Product Description

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish especially to thank Edward Weston for the many months of work and the understanding collaboration, maintained across a continent, which he has contributed to every stage of this book and the exhibition it accompanies. To Beaumont Newhall, for his invaluable aid in preparing the text and the bibliography, to Charis Wilson Weston, to whose writings and suggestions I am much indebted, and to Jean Charlot for permission to quote from his manuscript, I am particularly grateful. I wish also to thank Mrs. Gladys C. Bolt, Mrs. Gladys Bronson Hart, Mrs. Rae Davis Knight, Mrs. Mary Weston Seaman and Mrs. Flora Chandler Weston for lending the chloride, platinum, and palladio prints which represent Weston's earliest work.

Find “Edward Weston” (Pub. 2020) on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Edward-Weston/dp/1623261155?&_encoding=UTF8&tag=surpluscamera-20&linkCode=ur2&linkId=2ddc164e4bb958e738a72296e5927769&camp=1789&creative=9325

Edward Weston books on eBay: https://ebay.us/rFfkdm

Surplus Camera Gear participates in both the Amazon Associates Program and eBay Affiliate Program, designed to provide a means for us to earn by linking to their sites. When you click and/or make a purchase through a link on our website or posts, we may receive a small commission at no cost to you. This helps offset the cost of running the website.

EDWARD WESTON

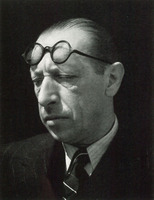

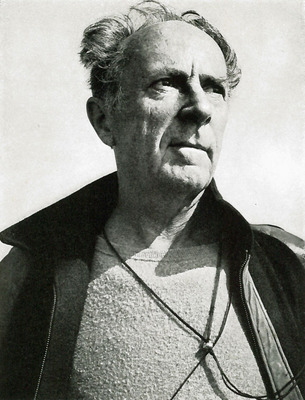

In 1902 two letters passed between Dr. Edward Burbank Weston and his sixteen-year-old son Edward Henry, who was spending the summer on a farm. The first, from Dr. Weston, accompanied a Bullseye camera and contained instructions on loading, standing with the light over one shoulder, and so on. The second, full of Edwards thanks, excitedly discussed his failures and a first success—a photograph of the chickens.

In 1902 two letters passed between Dr. Edward Burbank Weston and his sixteen-year-old son Edward Henry, who was spending the summer on a farm. The first, from Dr. Weston, accompanied a Bullseye camera and contained instructions on loading, standing with the light over one shoulder, and so on. The second, full of Edwards thanks, excitedly discussed his failures and a first success—a photograph of the chickens.From then on photography absorbed young Edward; his interest in school dwindled. When a magazine reproduced one of his sensitive little landscapes, such ambitions as wanting to be a painter or prizefighter vanished; he was definitely a photographer.

A livelihood, however, was something else. He came of generations of New England professional men. Edward, born in Highland Park, Illinois, in 1886, and his beloved sister Mary, were the first children born out of Maine for more than two centuries. His grandfather taught at Bowdoin College before moving to the Midwest to head a female seminary. His father, a general practitioner, found time during his rounds to teach in a local college. His mother, rebelling at the family tradition, left it as her dying wish that Edward should escape and become a businessman.

After three dull years as an errand boy in Chicago, Edward went on a two-week holiday to visit Mary, now married and living in Tropico, California. Enchanted by the place, he decided to stay, and immediately got a job with some surveyors, punching stakes in orange groves for a boom town railroad nobody intended to build. Later, carrying the level rod on the Old Salt Lake Railroad, he found mathematics in the hot desert sun overpowering. Returning to Tropico he set up as a photographer. With a postcard camera he went from house to house, photographing babies, pets, family groups, funerals, anything for a dollar a dozen. He fell in love and, full of responsibility, began seriously studying his profession. He at tended a "college of photography," learning a solid darkroom technique and how not to pose a sitter. For a year or two he held jobs with commercial portraitists, learning to make exact duplicate prints even from the poorly exposed and lighted negatives of his bosses.

In 1909 he married. Four sons were born: Chandler, 1910; Brett, 1911; Neil, 1914; and Cole, 1919.

In 1911 Weston built his own studio at Tropico. The customers who drifted in were delighted; even with his 11 x 14 studio camera, he was often able to make several exposures before they were aware of it. Posing by suggestion, he hid ungainly shapes in chiffon scarves or vignetted them away. The soft-focus Verito lens helped, and he retouched so deftly and with such regard for actual modeling that his patrons, unconscious of any change, were convinced they looked that well.

He was particularly successful with children. Trying to capture their activity, he bought, around 1912, a 3¼ x 4¼ Graflex. The curtains obscuring his skylight and sunny windows came down; the subtleties of natural light absorbed him. "I have a room full of cornersbright corners, dark corners, alcoves! An endless change takes place daily as the sun shifts from one window to another... All backgrounds have been discarded except those for special decorative effects, which are brought cut when needed."

He worked outdoors as well—his baby sons in the garden, Ruth St. Denis in Japanese costume standing in a shimmer of light and space with one spot of brilliant sun slanting across her cheek. From 1914 to 1917 he received a shower of honors. Commercial and professional societies awarded him trophies and asked him to demonstrate. Pictorial salons in New York, London, Toronto, Boston, Philadelphia, elected him to membership. Many one man shows at schools and clubs brought him further acclaim.

But he was not content. Something was wrong—with himself, with his hazy Whistlerian and Japanese approach. At the 1915 San Francisco Fair he first saw modern painting; radical new friends introduced him to contemporary thought, music, literature. His conservative friends and in-laws frowned; instead of settling down as a successful man and father he began to sport a velvet jacket and a cape. He ceased to send to pictorial exhibitions. His work was changing.

By 1920 the Japanese arrangements were violently asymmetrical. An attic provided semi-abstract themes of angular lights and shadows. By accident he discovered the extreme closeup; focusing on a nude, he saw, in the ground glass, forms of breast and shoulder so exciting that he forgot his customers. Groping, with occasional flashes of insight, he was still trying to impose his "artistic" personality on his subject matter.

Then, in 1922, the dark and exciting Tina Modotti took some of Weston's personal work to Mexico and exhibited it of the Academic de Bellos Aries. Her friends—Rivera, Siqueiros, the artists of the surging Mexican Renaissance—were enthusiastic. What is more they bought—a new experience for Weston. He decided he would go to live in Mexico.

In November he went East to say good by to Mary, whose husband was now with the steel industry in Ohio. The Armco plant, with its rows of giant smoke stocks, excited Weston to a series of photographs in which his own vision emerges unmistakably (p. 11). Mary urged him to go to New York and see the legendary masters there. In New York, with his mind full of the forms and rhythms of industrial America, he haunted the bridges and rode endlessly on the busses, looking up at the towering city. Articles on Alfred Stieglitz by Paul Rosenfeld and Herbert Seligmann had helped him discover why he was dissatisfied with his own work; actual contact with Stieglitz left him rather bewildered, though much moved by the photographs of Georgia O'Keeffe. His greatest enthusiasm was evoked by the clear structure of Charles Sheeler's architectural photographs.

In November he went East to say good by to Mary, whose husband was now with the steel industry in Ohio. The Armco plant, with its rows of giant smoke stocks, excited Weston to a series of photographs in which his own vision emerges unmistakably (p. 11). Mary urged him to go to New York and see the legendary masters there. In New York, with his mind full of the forms and rhythms of industrial America, he haunted the bridges and rode endlessly on the busses, looking up at the towering city. Articles on Alfred Stieglitz by Paul Rosenfeld and Herbert Seligmann had helped him discover why he was dissatisfied with his own work; actual contact with Stieglitz left him rather bewildered, though much moved by the photographs of Georgia O'Keeffe. His greatest enthusiasm was evoked by the clear structure of Charles Sheeler's architectural photographs.In August, 1923, he sailed for Mexico. With Tina, whom he had taught to photograph, he opened a portrait studio in Mexico City. His exhibition at "The Aztec Land" in October contained palladiotypes of industrial themes, sculptural fragments of nudes, highly individual portraits, people in contemporary life. The Mexican artists immediately accepted him. "I have never before had such intense and understanding appreciation... The intensity with which Latins express themselves has keyed me to high pitch, yet viewing my work on the wall day after day has depressed me. I see too clearly that I have often failed."

The three years in Mexico were years of ruthless self-scrutiny and growth. Unable in his halting Spanish to control his sitters by conversation, he took them out into the strong sunlight and watched in his for the spontaneous moment. A startlingly vivid series of heroic heads against the sky resulted—the keen-squinting Senator Galván at target practice, Rose Covarrubias smiling, with the sun in her downcast lashes. Commenting on the head of Guadalupe de Rivera (p. 13), Weston wrote (1924): "I am only now reaching an attainment in photography that in my ego of several years ago I thought I had reached long ago. It will be necessary to destroy, unlearn, and rebuild."

Between sittings—desperately poor, he was much confined to the studio for fear of losing a customer—he worked searchingly with still life—Mexican toys, pointed gourds, jugs—arranging them again and again in new lights, new relations. Within the courtyard, from the rooftop, whenever he could get away, he was at work with a more powerful and articulate clarity on the massive forms of Mexico; the vast landscapes, the huge pyramids (p. 12), the people-sprinkled patterns of the little towns.

More even than to the mental stimulation of such friends as Diego Rivera, Weston responded to "the proximity to a primitive race. I had known nothing of simple peasant people. I have been refreshed by their elemental expression. I have felt the soil." Close to them, confusions fell away. Eliminating every illusion, convention, process or device which impeded creation, he concentrated on vital essentials. "Give me peace and an hour's time and I create. Emotional heights are easily obtained, peace and time are not... One should be able to produce significant work 365 days a year. To create should be as simple as to breathe."

In 1925 he went to California for six months. Contact with his native land produced sharper rhythms, more complex motifs—industrials again, and unposed 8 x 10 portraits. Returning to Mexico with his son Brett, he photographed with a stronger feeling for light and texture the markets, the wall paintings outside native bars (p. 14), Dr. Atl standing beside a scribbled wall. Reviewing the Weston show at Guadalajara, 1925, Siqueiros wrote, In Weston's photographs, the texture—the physical quality—of things is rendered with the utmost exactness: the rough is rough, the smooth is smooth, flesh is alive, stone is hard. The things have a definite proportion and weight and are placed in a clearly defined distance one from the other... In a word, the beauty which these photographs of Weston's possess is photographic beauty!"

In 1925 he went to California for six months. Contact with his native land produced sharper rhythms, more complex motifs—industrials again, and unposed 8 x 10 portraits. Returning to Mexico with his son Brett, he photographed with a stronger feeling for light and texture the markets, the wall paintings outside native bars (p. 14), Dr. Atl standing beside a scribbled wall. Reviewing the Weston show at Guadalajara, 1925, Siqueiros wrote, In Weston's photographs, the texture—the physical quality—of things is rendered with the utmost exactness: the rough is rough, the smooth is smooth, flesh is alive, stone is hard. The things have a definite proportion and weight and are placed in a clearly defined distance one from the other... In a word, the beauty which these photographs of Weston's possess is photographic beauty!"With Tina and Brett, Weston traveled through almost unknown regions photographing sculpture for Anita Brenner's Idols Behind Altars and bold details of cloud and maguey for himself. But he was not and never could be Mexican; the time had come for him to return home.

His friends grieved. He had brought them on important stimulus and vision. Jean Charlot, in on as yet unpublished history of the Mexican Renaissance, wrote recently: "It was the good fortune of Mexico to be visited, at the time when the plastic vocabulary of the Renaissance was still tender and amenable to suggestions, by Edward Weston, one of the authentic masters that the United States has bred... Weston photographs illustrated in terms of today the belief in the validity of representational art... cleansed... of its Victorian connotations... He dealt with problems of substance, weight, tactile surface and biological thrusts that laid bare the roots of Mexican culture. When Rivera was painting The Day of the Dead in the City in the second court of the Ministry we talked about Weston. I advanced the opinion that his work was precious for us in that it delineated the limitations of our craft and staked optical plots forbidden forever to the brush. But Rivera, busily imitating the wood graining on the back of a chair, answered that in his opinion Weston blazed a path to a better way of seeing, and, as a result, of painting."

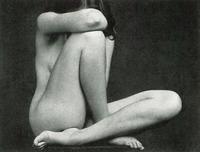

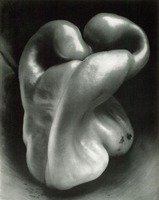

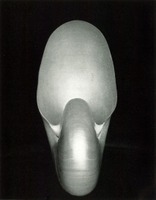

Back in Glendale, Weston missed Mexico and was at first unable to work. Then, in the studio of the painter Henrietta Shore, he picked up some shells of which she had been making some semi abstract studies. His mind was suddenly filled with the dynamic forces of growth, the vital forms and lucent surfaces of shells, fruits, vegetables. Often he worked for days on a single form in various nuances of natural light, seeking "to express clearly my feeling for life with photographic beautypresent objectively the texture, rhythm, form in nature without subterfuge or evasion in spirit or techniqueto record the quintessence of the object or element before my lens, rather than an interpretation, a superficial phase or passing mood..." He began to free the forms in space. One superb pepper came most thoroughly alive within the shimmering darkness of a tin funnel (p. 18). At the some time, with the same feeling: "I am also photographing a dancer in the nude... I find myself invariably making exposures during the transition from one position to the nextthe strongest moment."

Back in Glendale, Weston missed Mexico and was at first unable to work. Then, in the studio of the painter Henrietta Shore, he picked up some shells of which she had been making some semi abstract studies. His mind was suddenly filled with the dynamic forces of growth, the vital forms and lucent surfaces of shells, fruits, vegetables. Often he worked for days on a single form in various nuances of natural light, seeking "to express clearly my feeling for life with photographic beautypresent objectively the texture, rhythm, form in nature without subterfuge or evasion in spirit or techniqueto record the quintessence of the object or element before my lens, rather than an interpretation, a superficial phase or passing mood..." He began to free the forms in space. One superb pepper came most thoroughly alive within the shimmering darkness of a tin funnel (p. 18). At the some time, with the same feeling: "I am also photographing a dancer in the nude... I find myself invariably making exposures during the transition from one position to the nextthe strongest moment."With Brett, already at seventeen a remarkable photographer, he opened a studio in San Francisco. Cities increasingly oppressed him; in 1929 he welcomed a chance to move to Carmel among the Monterey coast mountains. Here he discovered what his friend Robinson Jeffers has described as "the strange, introverted, and storm-twisted beauty of Point Lobos." He photographed the writhing silver roots of cypresses and the strangling kelp, the starred succulents and monumental eroded rocks (p. 19), incandescent salt pools and winged skeletons of pelicans. Orozco, passing through Carmel in 1930, was so moved by these transcendent images that he arranged Weston's first New York one-man show that fall.

In 1927 the reaction to the first shells was surprise and dismay. Many people, including Rivera, thought them phallic. As the close-ups grew more subtle and powerful they struck beholders with the force of a revelation. Sober reviewers from Seattle to Boston discovered they were "art" and prattled of "miracles," "lowly things that yield strange, stark beauty." They declared Weston one of the most significant artists in America, in the twentieth century; they found him the peer of Picasso, Matisse, Brancusi, and Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1932 Merle Armitage brought out a handsome book of thirty-nine reproductions, The Art of Edward Weston. One-man shows swept spontaneously from Berlin to Shanghai, from Mexico to Vancouver. Unaided, with neither agent, group, nor institution to back him, Weston responded to innumerable requests with more than seventy different shows between 1921 and 1945.

With his first New York show, composed entirely of glossy prints—the shells and rocks demanded a brilliance and clarity beyond the bronze tones and matte surface of the palladiotype—Weston's concept stood forth clear and mature. "This is the approach: one must prevision and feel, before exposure, the finished print... The creative force is released coincident with the shutter's release. There is no substitute for amazement felt, significance realized, at the time of exposure. Developing and printing become but a careful carrying on of the original conception..." He had, and has, two cameras: an 8 x 10 view camera and a Graflex for portraits. There is one background, occasionally used behind a sitter. Settling his friends or clients somewhere, indoors or out, where the light is favorable, he lets them become themselves while he watches fleeting expressions and gestures. He uses one film, one paper. He tray-develops his negatives in pyro-soda, by inspection, bringing each one to the exact degree of delicacy or density he wants. Working under an overhead bulb with a printing frame, he makes only contact prints, dodging in areas beyond the scale of paper so deftly that the balance of light is never upset. Developed in amidol, scrupulously fixed and washed, more than half of the first prints from his negatives are exhibition quality. These prints are then drymounted on white boards and spotted. This is technique at its most basic and direct; the result of decades of experience, its emphasis is entirely on vision.

With his first New York show, composed entirely of glossy prints—the shells and rocks demanded a brilliance and clarity beyond the bronze tones and matte surface of the palladiotype—Weston's concept stood forth clear and mature. "This is the approach: one must prevision and feel, before exposure, the finished print... The creative force is released coincident with the shutter's release. There is no substitute for amazement felt, significance realized, at the time of exposure. Developing and printing become but a careful carrying on of the original conception..." He had, and has, two cameras: an 8 x 10 view camera and a Graflex for portraits. There is one background, occasionally used behind a sitter. Settling his friends or clients somewhere, indoors or out, where the light is favorable, he lets them become themselves while he watches fleeting expressions and gestures. He uses one film, one paper. He tray-develops his negatives in pyro-soda, by inspection, bringing each one to the exact degree of delicacy or density he wants. Working under an overhead bulb with a printing frame, he makes only contact prints, dodging in areas beyond the scale of paper so deftly that the balance of light is never upset. Developed in amidol, scrupulously fixed and washed, more than half of the first prints from his negatives are exhibition quality. These prints are then drymounted on white boards and spotted. This is technique at its most basic and direct; the result of decades of experience, its emphasis is entirely on vision.In his professional work he was still compelled to use evasions, enlarging the negatives onto 8 x 10 film with the old Verito lens stopped down just short of sharp. Printing the results on matte paper either eliminated retouching or hid the last traces of his almost invisible pencil work. This division between personal and professional standards bothered him. He campaigned among his sitters. More and more people discovered that the reality of one's own face, worn into character, quick with thought and feeling, the composition completed by mobile hands, has a curiously exciting quality. Friends liked the little prints and the unostentatious way they fitted into contemporary living. By 1934 he could at last hang out a sign: "Unretouched Portraits."

To thousands of photographers Weston was becoming a challenge; to his friends a sanctuary as well. To live more freely and simply than Thoreau, to work with a bare technique and produce brilliantly, to walk free, without help or compromise—these things are not easily achieved in the cluttered and frantic twentieth century.

His isolation was ending. Brett was changing from a prodigy to a co-worker and others were coming to share the stimulating companionship: Ansel Adams, whom they met as a pianist with some promising but immature photographs; Willard Van Dyke, who left his filling station for two weeks to study with Weston. These young photographers, wrestling with creative problems, discovering new subject matter, groping for their own approaches, began to form a group around Weston. The more they grew away from Pictorialism the more intolerable they found it that there should exist a system which put a premium on the obvious and the sentimental and consistently squeezed any honest or original thought into decadent impressionistic formulae.

The idea of organizing occurred to them. One night in 1932 Willard Van Dyke called a meeting and proposed Group being one of the smaller shutter stops and therefore associated with sharp focus. Lloyd Rollins, the new director of the M. H. de Young Museum in San Francisco, strongly encouraged the nascent group and held its inaugural exhibition in the fall of 1932. The most ardent protagonists, Adams and Van Dyke, both opened galleries, wrote vigorously for the press, and started a salon of "pure photography." With some of their pronouncements Weston could not agree. Gently, he withdrew. As an active spearhead, Group f/64 lasted only a year or two; as the violent peak of a great contemporary movement, its influence still persists.

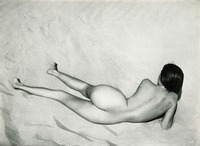

In the early 1930s Weston was alarming his friends by breaking away from the extreme closeup, doing clouds and villages in New Mexico, perspectives of a lettuce ranch in Salinas, the massive naked hills of the Big Sur. Then came, in 1936, a classic and majestic series. From their new studio in Santa Monica Edward and Brett worked together among the vast, wind-rippled sand dunes at Oceano which rose from deep swirls of morning shadow to stand dazzling and sculptural at noon, and sank again, bright-crested, into darkness (p. 22). Photographing across from one bank to another, with the sun along the same axis as his camera, Weston made a series of nudes in which a subtle line of shadow outlines the figure, rounding the living skin away from the harsh brilliance of the sand (p. 20).

In the early 1930s Weston was alarming his friends by breaking away from the extreme closeup, doing clouds and villages in New Mexico, perspectives of a lettuce ranch in Salinas, the massive naked hills of the Big Sur. Then came, in 1936, a classic and majestic series. From their new studio in Santa Monica Edward and Brett worked together among the vast, wind-rippled sand dunes at Oceano which rose from deep swirls of morning shadow to stand dazzling and sculptural at noon, and sank again, bright-crested, into darkness (p. 22). Photographing across from one bank to another, with the sun along the same axis as his camera, Weston made a series of nudes in which a subtle line of shadow outlines the figure, rounding the living skin away from the harsh brilliance of the sand (p. 20).The old longing to be free of clients led Weston to apply for a Guggenheim Fellowship "to make a series of photographic documents of the West." In 1937 he became the first photographer to receive this award. After twenty-six years he was at last able to concentrate on his personal work alone. He wanted to see if he could now meet what he considered photography's greatest challenge: "mass-production seeing." In most mediums, he felt, the artist is retarded by his process. He may not in a lifetime bring to birth a fraction of what he conceives. The photographer, realizing and executing in almost the same spontaneous instant, is limited only by his own ability to see and to create.

In California and the West his second wife, Charis, has the log of that journey—the planning of the $2000 grant down to the lost cent for a maximum of photography and travel, the canned foods stewed together over campfires, the slow drives through desert heat, mountain snow and coastal fogs. During those 35,000 miles, deeprooted thoughts and emotions began to coalesce into an image of the American West. It concerns the span of geological ages and the enormous savage earth momentarily littered with a brittle civilization. Elemental forces are the true protagonists in Weston's vision—forces which irresistibly produce a flower or a human being, erode granite, and make strange beauty not alone of skeletons but even of the decay of man's works.

In 1938 the Fellowship was extended. In the bore and simple darkroom of the little redwood house, built by Neil on a mountainside looking down over Point Lobos and the Pacific, Weston spent most of the year printing the fifteen hundred negatives made on his travels. The only duplicates were of unpredictable moving objects such as waves or cattle. Very few were discarded because they did not meet Weston's severe technical or esthetic standards. The series constitutes an astonishing achievement in variety of vision. Weston felt he had learned a great deal; he longed to go on.

In 1938 the Fellowship was extended. In the bore and simple darkroom of the little redwood house, built by Neil on a mountainside looking down over Point Lobos and the Pacific, Weston spent most of the year printing the fifteen hundred negatives made on his travels. The only duplicates were of unpredictable moving objects such as waves or cattle. Very few were discarded because they did not meet Weston's severe technical or esthetic standards. The series constitutes an astonishing achievement in variety of vision. Weston felt he had learned a great deal; he longed to go on.Returning rather reluctantly to Lobos, he discovered new themes—surf and tide pools, fog among the headlands starred with succulents and dark with cypresses. The stream of visitors began again. Weston photographed them more and more with the 8 x 10, sunning on the rocks (p. 29), against his house, among the ferns and flowers of his garden (p. 28).

In 1941 he was asked to photograph through America for an edition of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass. His aim was not to illustrate but to create a counterpoint to Whitman's vision. During the journey through the South and up the East Coast he found the land and the people weary, the civilization more strongly rooted in a quieter earth; he saw blatant power in industry everywhere, strength still standing in old barns and houses. In Louisiana he worked intensely on the decay and beauty of swamps, sepulchers, ruins of plantation houses. A miasma of gray light and smoke obscures the cities. In New York it seemed to wall him in.

The trip was cut short by Pearl Harbor. The Westons returned to Carmel, joined civilian watchers on the headlands. All Edward's sons were swept into the war. Lobos was occupied by the Army. Security regulations and gas rationing confined Weston to his backyard. Here he began photographing a beloved tribe of cats. Capturing their sinuous independence with an 8 x 10 produced an amusing series—and a formidable photographic achievement. With the robust humor and love of the grotesque that have always characterized his work, he also began producing a series of startling combinations—old shoes, nudes, flowers, gas masks, toothbrushes, houseswith satiric titles such as What We Fight For, Civilian Defense, and Exposition of Dynamic Symmetry.

On March 24, 1946, Weston will be sixty. For him, the long vista of growth focuses on today; in a recent letter he wrote, "I am a prolific, moss production, omnivorous seeker." His latest work surges with new themes. All the signs point towards fresh horizons.

The charter members of Group f/64 were: Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, John Paul Edwards, Sonia Noskowiak, Henry Swift, Willard Van Dyke, Edward Weston. Later members: Dorothea Lange, William Simpson, Peter Stackpole. Associates: Preston Holder, Consuelo Kanaga, Alma Lavenson, Brett Weston.

Product Videos

Custom Field

Product Reviews

1 Review Hide Reviews Show Reviews

-

Not an in-depth study of Weston's work

I was disappointed that there were not more examples of some of the series Weston produced. While the reproductions are good, I would have liked many many more of them.