Product Description

Wet Collodion Process

Either negatives or positives can be produced; and the latter, when taken upon thin enamelled-iron plates, are known as ferrotypes or tintypes. The following is a short résumé of the process:—A well-cleaned glass plate is coated with iodised collodion, and as soon as the collodion has set, this coated plate is immersed in a bath made as follows:

- Silver nitrate240 grs. (24 gms.)

- Potassium iodide1 gr. (0.1 gm.)

- Distilled water8 ozs. (350 c.c.)

Dissolve the silver salt in 2 ozs. (100 c.c.) of water, and the potash in ½ oz. (25 c.c.). Add the latter to the former, and add the remainder of the water. Filter, and test for acidity. If blue litmus paper is not turned red after an immersion of some short period, a few drops of a dilute nitric acid (1 in 12) should be added till the bath is decidedly acid. The plate is exposed whilst still wet, reckoning the speed of the plate as about 5 H. & D. For development either of the following may be used:

- Ferrous sulphate½ oz. (25 gms.)

- Glacial acetic acid½ oz. (25 0.0.)

- Methylated spirit½ oz. (25 c.c.)

- Distilled water10 ozs. (500 c.c.)

- Ferrous sulphate300 grs. (34 gms.)

- Glacial acetic acid200 mins. (23 c.c.)

- Formic acid (sp. gr. 1.060)100 mins. (11.5 c.c.)

- Methylated spirit240 mins. (27.5 c.c.)

- Distilled water10 ozs. (500 6.0.)

- Ferrous sulphate200 grs. (23 gms.)

- Glacial acetic acid180 mins. (20 c.c.)

- Lump sugar100 grs. (11.5 gms.)

- Methylated spirit240 mins. (27.5 c.c.)

- Distilled water10 ozs. (500 c.c.)

The Wet Collodion Process - The Getty Museum

Invented in 1851, the wet collodion photographic process produced a glass negative and a beautifully detailed print. Preferred for the quality of the prints and the ease with which they could be reproduced, the new method thrived from the 1850s until about 1880.

Photo Credits:

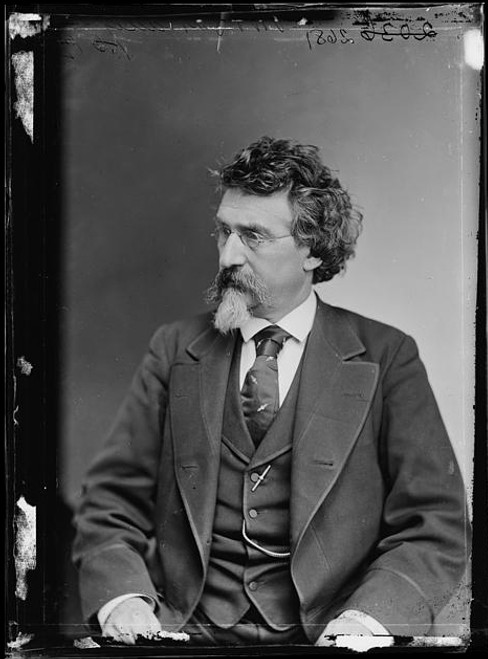

Mathew B. Brady, 1875

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Mathew Brady was one of the first famous American photographers, and his career was representative of many of the Civil War photographers. After opening his first studio, Brady deliberately sought to capture the “famous and powerful visages of the day”—and “it didn’t take long before leaders were coming to Brady, rather than the other way around.” Not only was this a good business opportunity, but he genuinely believed that “The camera is the eye of history,” and aimed to preserve these images of the wealthy and important for posterity.

Lewis Payne

Washington Navy Yard, D.C. Lewis Payne, in sweater, seated and manacled. Photograph of Washington, 1862-1865, the assassination of President Lincoln, April-July 1865. This photograph has background of dark metal, and was presumably taken on the monitors, U.S.S. Montauk and Saugus, where the conspirators were for a time confined.

President Theodore Roosevelt

Forms part of Brady-Handy Photograph Collection. In 1954 the Library of Congress purchased from Alice H. Cox and Mary H. Evans, the daughters of Levin C. Handy approximately 10,000 original, duplicate, and copy negatives. The Leven C. Handy Studio had been located at 494 Maryland Avenue SW, Washington, DC. Levin C. Handy (1855?-1932) was apprenticed at the age of twelve to his uncle, famed Civil War photographer Mathew B. Brady (1823?-1896). Handy became an independent photographer and over the years owned studios in partnership with Samuel Chester and with Chester and Brady. The Maryland Avenue studio was the most permanent and was the place where Levin Handy resided at his death in 1932. In the 1890s Brady himself had worked and lived at the Maryland Avenue address.